Five timing and video lessons from equine sports for track coaches by Carl Valle from FreelapUSA

Ask any track and field coach how much time they spend videoing their athletes and the answers will vary from, ‘None’ to ‘Every day’. With the rise of technologies and the ubiquitous availability of smartphones and video, we actually see a dark age in the digital age. The iPhone 6 cameras include an impressive high definition option and smooth slow motion at 240 fps (frames per second), yet for all of the advancements, classic films such as Guy Drut’s video and black and white photo finishes are still the standard in track and field. Ironically, over the last five years smartphone apps have dumbed down the process of filming because convenience diluted the skillset and decreased use of good methodology of capturing video. Anyone with a phone is now a videographer and anyone with an app is a biomechanist, and to make things worse, anyone with a few data sets is a statistician. To put a stop to the dilution of craftsmanship, I wanted to share how powerful the combination of electronic timing and video can be by using history and the Sport of Kings, horse racing. Horse racing does have a lot of problems in the sport and has baggage due to drugs and ethical treatment of the animals, but it does have a rich history of teaching coaches parallel lessons in athlete development. With intelligent filming and timing, coaches can improve the human athlete performances down the road more consistently and get athletes on the podium.

Currency – Coaches want a value to interventions

A common question that comes from sprint coaches is what is the technique, training or even nutritional intervention worth time wise? Any sprint coach worth their salt will want to see not only how much time the intervention is worth, but where the improvement is located in the race. Coaches are similar to engineers and realize that time dictates the value of any approach, and the weight room is a perfect example of this. Knowing that a power or speed to weight ratio exists, coaches know that added mass is only valuable when the changes in speed are worth it, especially at maximal velocity. Acceleration is far more trainable than top speed, so trade-offs must be carefully weighted for value. Other examples of this can be found in areas like electrical muscle stimulation (EMS) and improvements in speed. Looking at the research very few studies show up with elite sprinters, making one rethink the value of spending countless hours to get faster when efforts could go to getting leaner or getting more sleep. Sport psychology is now getting the attention it needs, showing how the power of motivation and toughness can be actually measured with different biochemical and brain evaluation methods. Coaches should pursue what works strongest, based on the value of the interventions, not on tradition only.

Fusion Tip 1- Create Your Currency Based on Time and Space

Splits at maximal speed and splits at other points of training distances during the race are excellent sources of value in designing training interventions. Video and electronic timing dissects and distills which parts of the performance are limiting improvement, and give direct options based on effectiveness. A great example of the importance of addressing body composition and body mass in general, is looking at the acceleration and maximal speed velocities of sprinters compared to their weight and body composition. Athletes may excel at early departure, but if their mass and body composition are not optimized, clear relationships can be seen at very high-speed video and extrapolated into values on the clock. The clock is the best judge on what is important, because the best time is what wins in the end for the running events. Distance is similar to the field events, and many of the jumps and even the javelin has a strong correlation to horizontal speed and ultimate performance. Timing and videoing purges and prunes what is not effective in making significant improvement and naturally creates a hierarchy of importance to interventions.

Discovery – Coaches want Insight

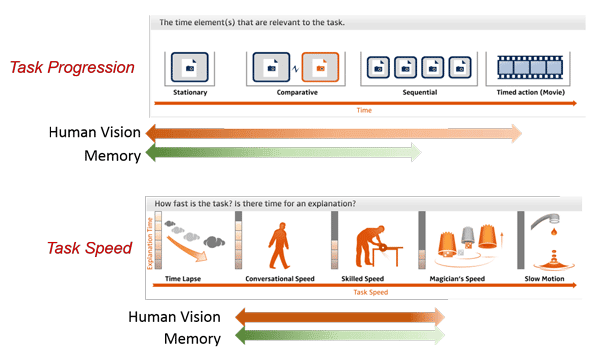

Video is the ultimate foundation of truth if done right, removing the debate to what happened. A good argument for the first real use with video in sport can be traced back to the question of horses and their locomotion. In 1872, Eadweard Muybridge was commissioned by Leland Standford, the former governor and tycoon who founded Stanford University, to find out if all four legs were in the air during a horse’s trotting motion. While it took years to create a full-time series, all it took was one slide to deliver the answer that horses indeed had unsupported transit. These were the first shots of the modern technology in sport. Coaches have amazing naked eyes, but the video slowed down to a stop reveals the truth of what is going on in that exact moment, telling a clear story of what is going on. A great example is the triple extension far beyond the center of mass with sprinting, and evidence now points that the faster sprinters are extending less and are not producing power close to toe-off.

Fusion Tip 2- Create Your Maximal Velocity Checklist

A simple and direct way to get applied biomechanics is to see the stride parameters of maximal velocity with electronic splits ranging from 10-30 meters in length. By calculating maximal velocity in meters per second, a coach can see the transfer of key technical areas such as posture, knee flexion, hip extension, and knee flexion during the support phase. Studies from Ralph Mann and others are extremely valuable, and coaches can research grade data when filming sprints from the side and zooming in. It is essential that maximal speed is filmed at a squared angle and far enough away to get valid stride angles. The easiest way to do this is place the camera in the middle of the infield of the track and the midpoint of the fly zone when filming. This is enough to see improvements and all you need is a few strides to get useful data.

Milestones – Coaches want turning points or achievements

Anyone training an athlete is pursing either and adaptation (improvement in the body) or acquisition (improvement in motor learning or technique). Someone’s ability is fleeting during a career, so some areas are more permanent, as the ability to execute a specific action over and again. A major improvement and sometimes regression is a milestone. Milestones are clear points in time that jump out, and are defined by the beholder looking from the inside and outside respectively. A low level milestone can be a young athlete learning to attach a hurdler versus jump it by diving in with a specific posture, or it can be an elite athlete in the discus blocking every through properly versus at random. A milestone is not a goal outcome, but a clear part of training or performance that places the athlete in another class or realm of achievement. In horse racing and other equine sports, the best trainers don’t let the animal compete unless they hit specific benchmarks or other criteria that make the next level a wise investment. Learning from the pain medications risking lives of the horses, milestones in rehabilitation should most likely be training, not management of pain. Video analysis can be a wonderful option in sports medicine, an area growing in clinics.

Fusion Tip 3- Profile the performances and races with simple metrics

When doing race or performance analysis, several examples exist but one of our favorites is looking at the mean, median, and mode of key performance indicators. Why is a high jumper great once and their average performance mediocre? The combination of technical and output metrics profiles not only what an athlete is made of, but why they are that way. Examples in sprints and hurdles are splits, jumps are running velocities relating to jump mechanics and throws is timing and key positions. Distance is usually much more physiological, but coaches can do more subjective and qualitative analysis with video and race splits when training data and testing is done before competitions.

Innovation – Coaches want change that improves outcomes

Like horse racing, the sport of track and field hasn’t changed much besides the technology of the running surface, and the implements being assisted with favorable adjustments, like a pole vault. Coaches know that sport is the younger sibling of war, and much of the competitive approaches and the origin of track and field events can be traced to battle tactics and approaches. The origins of horse racing are still debated, but before Roman stadium races the war chariots of ancient Egypt (who themselves copied others) when designers at that time manipulated the amount of spokes to improve speed by reducing weight of the wheels. When technology stagnates because of rules or creativity lag, coaches must go to the drawing board and rely on imagination or sometimes try old tricks. A great example of innovation now is the men’s 110m hurdles, with many of the elite hurdlers using seven steps instead of 8. Robles may have coined the 7-step approach in his breakout years of the late 2000s but decades earlier hurdlers were using the seven-step approach but were not breaking records. The spectacular year of 2008 for Dayron Robles brought the new approach to hurdle one to the world’s elite, and more often than not we see seven steps making the rounds of top hurdling.

Fusion Tip 4- Innovate with Quantified Experimentation

Revolutions like the Fosbury flop and other innovations are rare, so it’s best to look at where small improvements can be made and focus on making changes to areas that are more obvious. Nobody has the secret but the best coaches are usually looking at ways to get better by addressing the entire event rather than just finding a magic bullet. Small experiments with measured performances and video are great ways to see if things are trending up or if ideas need refinement. Nobody knows where the next evolution is going to come but the best idea is to have a small experiment and let the ripple effects take over.

Integration – Coaches want things to play nice

Rarely does a coach want just one set of data in isolation, most want meaning by looking at a reasonable spread of data. Multiple data sets push and guide coaches to see more meaningful relationships by cross-referencing information and seeing trends. The cardinal example of fusion in sport analysis for 2010 was the integration of kinetic data from Myotest with Scott Damman using power indices for weight and jump training with dartfish.tv. The presentation at the USOC in Colorado Springs foreshadowed his later developments with other sensor technologies with Assess2Perform, a standard most coaches want. The CSV reader from Dartfish is a true quantum leap, as it enables one to see the forces in power development to come alive with video. Integrating video and kinetic data will be the new norm as data sources become easier to capture and simpler to merge. Horse training for years has appreciated the need to see how physiological data and speed interchange, and endurance athletes now need more and more mechanical guidance in order to keep running economy high and injury rates low.

Fusion Tip 5- Add physiological, chronological and kinetic data to video

Fatigue, critical power, and velocity are not difficult to measure and combining them on video is a breeze. It can be summarized that simply adding a line plot to the video tells a story without having to say a single word. The end game to the matter is that every event in track and field is time and distance and adding velocity, physiological monitoring, and power to kinematic (read ‘technique’) is straightforward and should be standard by now. Speed is a crucial factor to every event in some form or another and timing and video are the most natural of pairings.

Final thoughts

Track and Field has a long and rich tradition with technology, timing and video. Coaches looking to close the gap in performance should always think about sharing video and placing an emphasis on solid data sets like splits and training loads. Athletes have a responsibility to understand and own their technique breakdown as well as their outputs in both the track and field and of course the weight room. Video is not just for coaches and athletes, since film is part of the diagnosis to problems and screening and return to play strategies are more effective when a simple video clip is shared with all parties. In closing, it’s no longer OK to say we are too busy to get video and do analysis when a coach and athlete can pick up a smartphone and capture, analyze, and share an moment in time.

Comments are closed.